The Challenge of Falling Grocery Inflation for Suppliers

Both Coles and Woolworths released their FY24 results this week and, while there has been much discussion about the headline sales and profit results, the numbers that caught my eye were the grocery inflation figures that Coles reported.

Shelf prices increased at a rate of only 1.5% p.a. in the second half of FY24, down from 2.9% in the first half and a whopping 6.9% in FY23. This is a dramatic turnaround from where we were a year ago. Given the trajectory, and easing cost pressures, I wouldn’t be surprised to see the next half’s grocery inflation number come in below 1%.

Changes in retail prices are a direct result of changes in manufacturer sell prices. So falling inflation means that retailers are accepting fewer and smaller cost increases from suppliers that they were the previous year. This trend will continue over the next 12 months, particularly with lower commodity prices and increasing labour availability easing cost pressure for producers.

Coles Retail Price Inflation

Source: Coles Annual Reports

Decreasing Commodity Prices

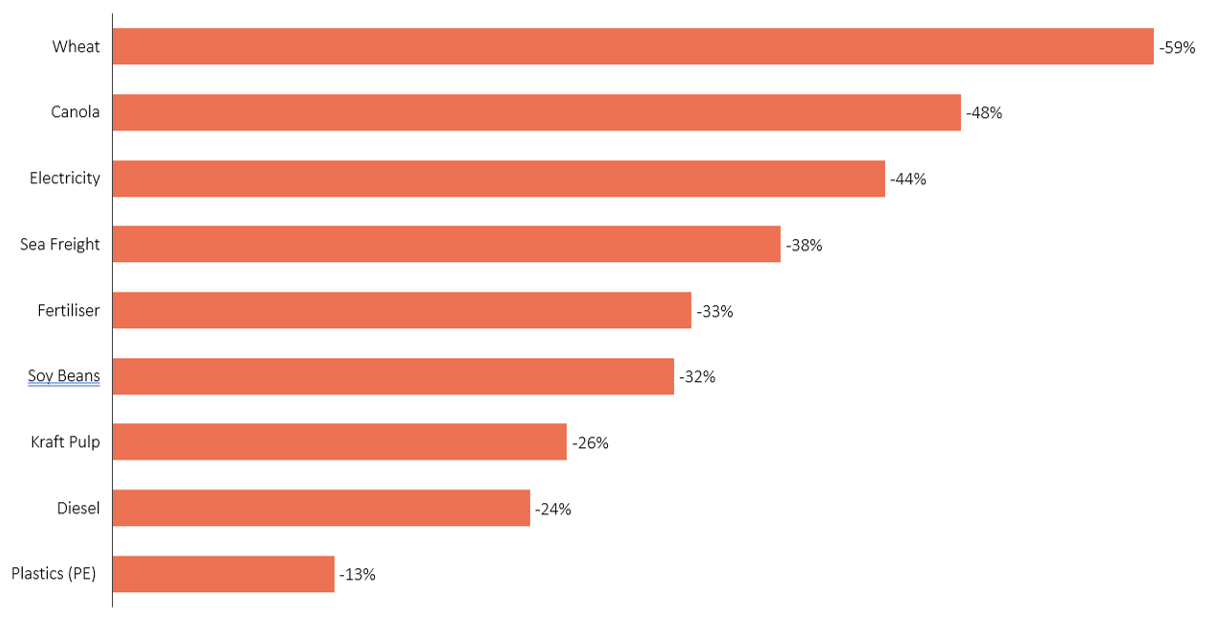

The good news for producers is that the prices of almost all major soft commodities have fallen dramatically since their peak in FY23, including wheat and grains, electricity, sea freight, fertiliser, plastics, cardboard and diesel.

This will go a long way towards easing margin and cost pressures for producers. However, falling commodity price indexes don’t always translate automatically to cost reductions. Suppliers of key inputs to food manufacturing, such as packaging, ingredients or transport tend not to offer cost reductions off their own bat. Like any other business, they look to maintain prices and margins as long as they can and will only pass through cost reductions when they are pushed to do so.

This is where Procurement comes in. A comprehensive sourcing program that introduces competitive tension via a rigorous, structured RFP process is the most effective way to reduce the cost of key inputs and to maximise the benefit of falling commodity prices. We’ll cover this topic more in a later article.

Commodity Price Decreases from FY23 Peak

Sources: Chicago Board of Trade, ICE Futures Canada, Australian Eastern Young Cattle Indicator, Global container freight rate index, DAP Spot Price US Gulf, Global Dairy Trade, Diesel Terminal Gate Prices

Improving Labour Supply

The other area we’ve taken a look at is labour rates and supply. Many food and agribusinesses have struggled with labour shortages over the last few years. It has been difficult to attract and retain skilled staff, particularly in regional remote areas. Consequently, companies have been holding onto any excess staff that they do have, or haven’t focused as closely on efficiency and labour optimisation as they typically would. This, along with a strong economy, has resulted in a surge in demand for labour and significant increases in cost.

The good news is that, after flat lining for several years, the total labour market has increased by 1.2m workers (9%) in the last two and a bit years. With increasing supply and more competition for available jobs, labour cost pressures will moderate this financial year.

Total Australian Labour Force (Million Persons)

Source: ABS 6291.0.55.001 Labour Force, Australia

In summary, food and grocery inflation is falling rapidly, making it difficult for suppliers to justify price increases. But lower commodity prices and an improving labour market will allow companies to reduce costs and maintain their margins.